Prologue: A Biographer Worth Respecting

First I'll say this– I greatly respect Ron Chernow. The man's a titan of contemporary biography. That makes this post harder to write.

Especially because, in 2nd grade, if you'd asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would have answered: historian. Geography was my jam. I enjoyed pulling down random letters of World Book Encyclopedia volumes and cruising the entries, I memorized all U.S. state, world capitals, and their flags by the time I was in 3rd grade. (I was that kid.)

To me, being a historian was peak intellect. You were a time traveler living among the ghosts of great people, documenting their lives and adventures, striving to translate their wisdom and knowledge to the present. I wouldn't have said it that way back then, but that's what I felt.

Part of being a messenger from the past means transmitting the thoughts and words of its inhabitants as faithfully as possible. This includes contradictions and shortcomings, not just reading the comforting correspondence. Because how else can we learn from the lessons of the history if we don't view it through as clear a lens as possible? It is the historian (by way of the biographer) who polishes that viewport to antiquity that allows us the cleanest reproduction of those who lived before.

Few have done it better than Ron Chernow.

Don't know who he is?

He's become America's Biographer. Known for meticulous research, language clarity, and academic rigor, historically he's tackled America's icons with a style that literally feels (at times) like speaking to the dead.

Titan (John D. Rockefeller Sr.), Grant, Washington: A Life, and yes, Hamilton (the one that spawned the play, musical, movie, and probably it's own mobile game) were all written by him.

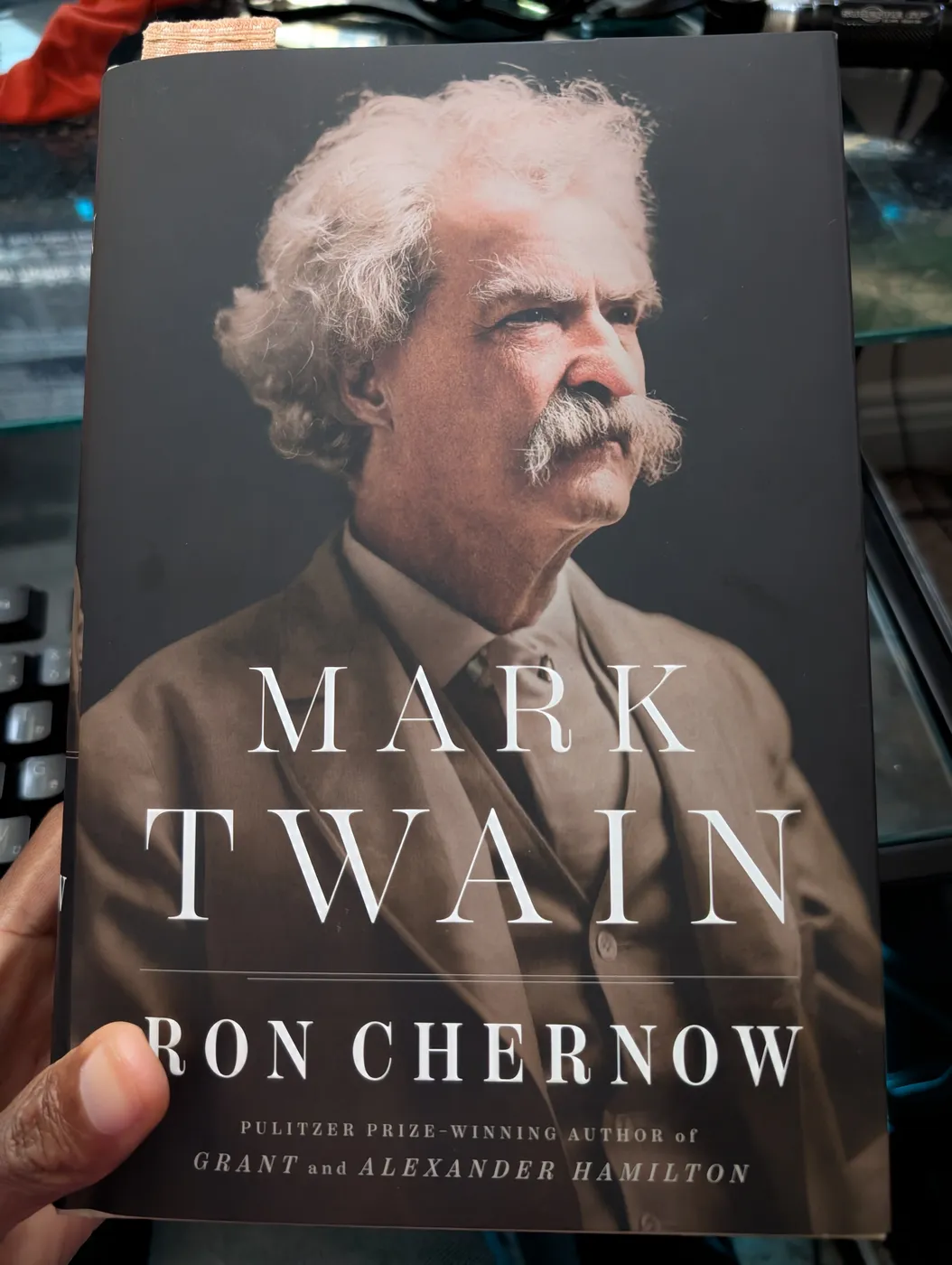

So when I heard the subject of his next dictionary-sized work would be Mark Twain, I knew I would read it.

I pre-ordered the book back in April 2025, eager for another Chernow masterpiece. When it arrived, I felt that familiar thrill–- the satisfying heft of a Ron Chernow biography. The man doesn’t write slim rags. These are bookends. Other titles lean on it. You feel the years of research in the spine before you even open it. I remember setting it on my shelf, thinking, I can’t wait to read this.

But life got busy. Months passed, other writing projects came and went.

When I finally pulled it down, five months later, I cracked the cover and felt that rush of anticipation again– that old promise of stepping into the time warp with someone who knows how to guide you through it.

Yet after two chapters, I couldn't stomach anymore: I DNF'd. This essay explains why.

Now this isn't one of those "the-author's-book's-bad-so-the-author-is-bad/problematic/cringe-too" hot takes. It's also not a review, because I obviously didn't complete the book (it's nearly 1000 pages long!).

I'm not attacking Chernow as a person. I respect his commitment to American history and the craft of writing. Someday I hope to be so respected and so paid. Dunking on media has become the preferred sport online today, and these days I can only scrape the rim, so I won't spring to that.

What I do want to do is read between the lines and ask: what the hell happened here?

Why does Mark Twain read like a boardroom of white executives– influenced by AI analytics, and data recommendations– possessed Chernow's computer and pieced together a biography with fully-evolved energy, but as toothless and inoffensive in its predictability for audience appeasement as an untrained AI-generated response?

A puppet show, with the hairy arm of the controller visible: how come this book reads like high school theater, instructing readers how to think about a controversial figure like Twain?

Let's talk about the tragedy and fear behind Mark Twain (2025).

I. Trouble Begins With a "E" (for Enslaved)

It started with enslaved person. After I read it three times in the Prelude, I began to smell the sour before the shit. Before this book, I had never seen or heard it prior. But something in me had a strong dislike for it.

I knew what Chernow meant by it. I, of course, understand the intent– to humanize those held in bondage, to remind readers that slavery was something done to and forced on people, not an identity they owned.

But when I saw the phrase on page 4, my gut bubbled. Not in horror at the history, but in irritation at the language itself.

What for?

Enslaved person doesn’t sound human inspired; it sounds human engineered. It’s committee-approved jargon– a linguistic Band-Aid pressed over a centuries-old wound. Classic top-down creation of language used by and for "progressive" elites, not by the population it's meant to define or influence.

As a descendant of slaves, I don’t need my ancestors softened into syllables. “Slave” is brutal, yes, but it’s true. This is the language we know. Changing the word may assuage modern white guilt among themselves, but doesn't erase the legacy of slavery.

Rebranding brutality doesn’t redeem it. It sanitizes it.

That moment told me exactly what kind of biography I was holding: one where the moral framing would matter more than the man.

II. Biography as Moral Performance

By the time I hit chapter two, it was clear Chernow wasn’t writing about or for Twain– he was writing about us. Or rather, about who we want to believe we are in 2025.

The book reads like a historical sermon. One Twain himself would've ducked out on to go write about how Biblically repressive and boring it was. It reads like a 19th-century life filtered through 21st-century fear of cancellation/liability/reputational ruin/online mobs/trolls/and AI memes. Could be one or all of these that twisted Chernow's arm to publish such a paint-by-numbers presented biography.

Every risky moment is cushioned by “don’t worry, reader” disclaimers– soft reassurances that Twain’s skepticism toward religion or his racial blind spots can be explained, contextualized, or morally rehabilitated.

Twain was never a racist, never!

He was only a victim of abhorrent Southern norms of his time. Like any human, he absorbed the fallibilities of his tribe. Nurture, NUTURE, not nature. Couldn't be.

And even if he was responsible for a few eh hem: "off-color", remarks over the years, he made up for it when, "He experienced tremendous growth in his attitudes, graduating from the crude racist gibes of his early letters and notebooks to a friendship with Frederick Douglass, financing a Black law student at Yale, promoting the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and denouncing racial bigotry in a wide variety of forms."

See? He loved niggas! He even had a famous black friend! How could he be racist?

Chernow really sets up this narrative from the beginning. Twain, raised in the wilds of a slavery-sympathetic society, but civilized to views closer to our own by the end of his life, is the logline. A virtuous arc so complete it could almost be Christian canon.

He does this as he cherrypicks lines from Twain's later years on slavery and the "...town that still had slave auctions and minstrel shows with racist impersonations of Banjo and Bones..." to place in the part of the mythic origin story of Twain's restless youth.

This strategic assembly of Twain's character is a blow-up Frankenstein, fit for the house on the corner at Halloween, not serious historical inquiry.

It’s not that he misrepresents the facts. In standard Chernow fashion, the book is exhaustively researched, pulling from countless archives of the witticist's notes, letters, and journals.

It’s that he can’t resist interpreting Twain's famous foibles into safety. Every contradiction becomes a moral lesson. Every flaw, an opportunity for the coming redemption story. By the second chapter, the rhythm felt mechanical– an ethical pulse so steady it drowned out Twain’s voice, making me wonder if this was written for posterity or modern conformity.

III. The Grant Problem and the Great Capitulation

I bought this book because I’d admired Chernow’s Grant. That biography balanced complexity with reality. It showed triumph and ruin side by side. No moral sanding, no ideological cushions. Just a man and his century, tangled together. Grant was a legendary war hero, decent president during the rough and wild post-Civil War years, yet a man who was often duped and naive in personal matters.

But Mark Twain reads like it was workshopped to offend no one. For instance, Judge John Clemens, Twain’s father, is reduced to a loveless patriarch in the opening pages. The archetypal cold, failed man of ambition.

Meanwhile, his wife, Jane, becomes the radiant proto-feminist, spirited and sympathetic, reinforcing a common message in today's media landscape: "women are wonderful" "men are monsters." Together they form a binary too tidy to be believable.

The distortion of people to fit a simplistic narrative, grated. Judge Clemens’s mobility, his relative wealth, his risks, flat as a flapjack in favor of a morality play.

This safe framing has crept into too much modern history writing and media. The impulse to turn the past into allegory for the present, to preempt every critic by embedding apology in the prose, makes it difficult to view the past with critical evaluation. After all, how can you question it, if the facts are arranged in the most morally righteous order and according to 21st century sensibilities?

Even a historian of Chernow’s stature isn’t immune to the pressure of our algorithmic age. After ten years of research and freedom from editorial interference, he still yielded to the pressure of the times.

IV. "Twain and the Multiverse of Mischief" Coming to Netflix 2026

Read enough of Mark Twain and you start to see a pattern: many paragraphs begin like an opening for an episode of a Twain Netflix show.

“Even as a boy, Sam Clemens had a pronounced streak of nonconformity.”

“This willful boy had a penchant for doing shocking things.”

“Twain was fond of recounting a story about the measles epidemic…”

"The father who found humor in nothing spawned a son who found humor in everything."

"Luckily... Jane Lampton Clemens provided compensatory warmth and brightness in her son's life."

"As the years passed and darker truths about slavery surfaced in his memory, Twain remembered savage punishments inflicted upon the Black population..."

See? We already got half a season right here.

Every anecdote becomes prophecy. Every mischievous deed, a lurking legendary action. Chernow can’t resist turning the boy into the destined humorist. It’s as if he’s building Twain: Origins for Netflix, complete with the glowing runes of adjectives circling his head as he floats down the Mississippi, eyes white, wind whipping his stringy hair around like an aura-maxxed anime hero.

Ironically, there’s little irony, no ambiguity, no danger– just the neat inevitability of a Marvel-esque hero arc, neatly packaged and framed for your distracted consumption. The prankster boy becomes the destined man of wit, every ill-thought hijink proof that greatness was preordained, and carried out with heart. Roll credits.

Twain would have despised this. He spent his career mocking canonization. And Chernow sculpted him a marble pedestal.

V. Twain on Twitter (or, the Roast from Beyond)

When I'd finally had enough– two chapters in– I realized I’d spent more time ranting than reading. That’s when I knew I was done.

But in that irritation, I had a thought: what would Mark Twain say about this biography of his destined greatness, lacquered in white paint and presented so innocuously as a passing cloud?

I imagined him alive in 2025, scrolling through his own biography, aghast at the sanctified portrait staring back.

On X (formerly Twitter), he’d say things like:

"A biography should exhume the dead, not bury the living under modern speech."

"History, when scrubbed clean for modern company, looks less like truth and more like taxidermy."

"Chernow’s Mark Twain reads like an obituary written by a man afraid the corpse might disagree."

"The biography is thick as a Bible, but thin as newspaper. I'd skim it in the morning and sell it by noontime."

It became a full parody thread: Twain the verified ghost, posting from the afterlife about being morally rehabilitated by the living. It was cathartic writing those, and truer to Twain’s spirit than much of the content in Chernow’s 1000 pages.

VI. The Death of Nuance

What bothers me most isn’t Chernow’s scholarship– it’s the instinct that drives it.

The compulsion to pre-chew the past so modern readers won’t choke, to provide guardrails on a man who lived by few, rubbed me wrong.

This is biography as moral PR: long, polished, safe, and deeply afraid of backlash by modern standards. The lack of courage in the construction of it is dispiriting.

Twain was contradiction. He was the faithful cynic, the moral skeptic, the sinner with a conscience. He wrote in the gray space between hypocrisy and revelation.

Stomp that out, and you don’t just misread Twain, you miss the entire point of writing his biography in the first place.

VII. Closing Thought

I didn’t finish Mark Twain. But in putting it down, I remembered:

A bad book can still be a good teacher– especially when it spurs you to write.

Chernow gave me something Twain would’ve approved of:

A reason to laugh at the sanctimonious, to mistrust the moralizers, and to remember that truth, like humor, can’t survive over-editing.

If virtue had a word count, Mark Twain would be a secular religious tome with footnotes.

Twain, given access to social media, might've gotten as far as I did, closed it, shitposted about it, then laughed.